Quick Facts

Country Name: Burkina Faso (“Land of the Honest People”). Formerly known as Republic of Upper Volta, with the name Burkina Faso adopted in 1984.

Geographical Location/Size: A landlocked country located in Western Africa. It is bounded by Mali to the north and west, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, and Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Togo to the south. Its geographical size is estimated at 105,870 square miles.

Population: Estimated at 19.19 million (2019). The annual population growth rate is estimated at 3% (2019).[1]

Ethnic Groups: Mossi 52%, Fulani 8.4%, Gurma 7%, Bobo 4.9%, Gurunsi 4.6%, Senufo 4.5%, Bissa 3.7%, Lobi 2.4%, Dagara 2.4%, Tuareg/Bella 1.9%, Dioula 0.8%, unspecified 0.3%, other 7.2% (2010 est.)

Languages: French (official, although not widely spoken). The majority of the population speaks Moore, the language of the Mossi. Dyula is widely spoken in commerce.

Religion: Muslim 61.5%, Roman Catholic 23.3%, traditional/animist 7.8%, Protestant 6.5%, other 0.9% (2010 est.)

Capital: Ouagadougou. Population size is 2.2 million (2015). Located in the center of the country, it is the administrative capital and the seat of government.

Currency: West African CFA Franc, which is officially pegged to the Euro.

Government Type: Presidential Republic. President is chief of state, with the Prime Minister, the Head of Government, appointed by the President and approved by the National Assembly. The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and can serve up to two consecutive terms. The legislative branch of the government is represented by the National Assembly, whose members are elected by universal suffrage for five-year terms.

Administrative Divisions: 13 regions: Boucle du Mouhoun, Cascades, Centre, Centre-Est, Centre-Nord, Centre-Ouest, Centre-Sud, Est, Hauts-Bassins, Nord, Plateau-Central, Sahel, and Sud-Ouest.

Legal System: Civil law based on the French model and customary law.

Chief of State: President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, age 62 (since November 29, 2015). President Kabore, a French-educated banker, previously served as prime minister and speaker of parliament under long-time President Blaise Compaore, until he won the November 2015 presidential election. Kaboré, a long-standing Compaore loyalist, in 2014 resigned as chairman of the then-president’s Congress for Democracy and Progress party over the former President’s plans to amend the constitution to extend his 27-year rule. In January 2014, was instrumental in founding the People’s Movement for Progress (French: Mouvement du Peuple pour le Progrès, MPP), which he leads.

Head of Government: Prime Minister Christophe Joseph Marie Dabiré, age 70 (since January 24, 2019). Dabiré, an economist, had previously represented Burkina Faso at the West African Economic and Monetary Union, and had served as a minister under former president Blaise Compaore from 1994 to 1996, with Kaboré holding the title of Prime Minister during that period. He is a member of the MPP.

Cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Prime Minister.

Opposition Leader: Zephirin Diabre, age 59. In the November 29, 2015 elections, his party, Union for Progress and Reform (UPC), came in second with 29.6% of the votes. An economist, he served as Minister of Finance in the 1990s.

Legislative Branch: Unicameral National Assembly (127 seats; members directly elected in multi-seat constituencies by party-list proportional representation vote to serve 5-year terms).

Elections: With last elections held in November 2015, the next elections are scheduled for November 2020.

Judicial Branch: Supreme Court of Appeals, Council of State, and Constitutional Council. The Supreme Court judge appointments are controlled by the president of Burkina Faso. Subordinate courts include the Appeals Court, High Court, first instance tribunals, district courts, specialized courts relating to issues of labor, children, and juveniles, and village (customary) courts.

Significant Historical Events

1896: Kingdoms constituting Burkina Faso became a French protectorate, later known as Upper Volta.

August 5, 1960: Upper Volta gained independence from France, with Maurice Yameogo elected as president.

October 3, 1965: President Maurice Yaméogo was re-elected without opposition.

January 2, 1966: President Yaméogo declared a state-of-emergency (which lasted until July 7, 1978).

January 3, 1966: President Yameogo was overthrown by Lieutenant Colonel Sangoule Lamizana, who became president on January 7, 1966. He also held the additional position of Prime Minister from February 8, 1974, to July 7, 1978.

June 21, 1970: A new constitution went into effect.

February 8, 1974: President Lamizana dismissed the government of Prime Minister Kango Ouedraogo, dissolved the National Assembly, and suspended the constitution. On February 11, President Lamizana appointed himself as prime minister.

November 25, 1980: President Lamizana was ousted in a military coup led by Colonel Saye Zerbo.

November 6-7, 1982: Colonel Zerbo was deposed in a military coup led by Major Jean-Baptiste Ouedraogo, who took control of the government on November 8th.

January 10, 1983: Captain Thomas Sankara was appointed as prime minister.

August 4, 1983: President Ouedraogo was deposed in a military coup led by Prime Minister Sankara.

1984: Upper Volta renamed Burkina Faso.

October 15, 1987: President Sankara was killed in a military coup led by Captain Blaise Compaoré (who remained in power for 27 years).

Captain Compaoré formed a transitional government on June 16, 1990. A new constitution was approved in a referendum on June 2, 1991. Blaise Compaoré of the Popular Front (PF) was elected president without opposition on December 1, 1991.

Late October 2014: President Compaore resigned, following street protests against his push to amend the constitution’s two-term presidential limit. He was succeeded by Acting President Kafando.

November 29, 2015: Presidential and legislative elections were held, in which Roch Marc Christian Kaboré was elected president.

January 2016: Paul Kaba Thieba was appointed as prime minister.

January 19, 2019: Prime Minister Paul Kaba Thieba and his government resigned. On January 24, was replaced by Christophe Joseph Marie Dabiré.

Drivers of Instability

In Burkina Faso, drivers of instability consist of crises in areas such as climate, economy, refugees, politics, and security (with insurgencies by several terrorist groups).

Climate Change

As a landlocked and mostly desert country, Burkina Faso experiences recurring droughts, landscape desertification, and soil degradation, which severely affect agricultural activities (particularly overgrazing), economic development, and population distribution, with high internal population displacement. This has resulted in chronically high rates of food insecurity, food scarcity, inflated prices, and under-nutrition.

Economic Conditions

Burkina Faso is one of the world’s poorest countries, with an estimated 45 percent of the population living on less than $1.25 a day.[2] A landlocked Sub-Saharan country, it has limited natural resources and a weak industrial base. The economy is heavily reliant on subsistence agriculture and livestock-raising, with close to 90 percent of the population employed in the sector.[3] Cotton is the country’s most important cash crop, while gold exports have gained importance in recent years. The economy is also highly vulnerable to severe weather events, especially intermittent droughts, causing extensive migration from rural to urban areas within Burkina Faso, and to neighboring countries, most notably Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. An estimated 1.6 million people were migrants abroad in 2013 (approximately 10 percent of the population at the time), with about 1.5 million of them living in Cote d’Ivoire.[4] In another negative economic indicator, industrial growth is hampered by the small size of the market economy and by the absence of a direct outlet to the sea. To attract foreign investment, the government has privatized some state-owned entities.

Main imports include petroleum, chemical products, machinery, and foodstuffs, which come from African countries, as well as from China and France. The relatively small amount of exports are led by gold ($1.87 billion annually), accounting for about 79.1% of the total export revenues (and 4th largest producer in Africa), and raw cotton ($180 million annually), which accounts for an estimated 7.6% of total export revenues.[5] Both are especially vulnerable to sharp fluctuations in their respective worldwide commodity prices.

In terms of infrastructure, access to sanitation and electricity is poor, while insufficient investment in education and infrastructure limit economic development.

Refugee Conditions

Refugees constituted another source of instability in Burkina Faso. Regional instability affecting Burkina Faso and its conflict-affected neighbors, particularly Mali and Niger, has resulted in a massive influx of refugees and internally displaced populations which has aggravated not only the vulnerability of such refugees, in general, but relations with their host populations, as well, over issues such as access to scarce natural resources, such as water. According to the UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, in 2019 there were an estimated 170,447 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Burkina Faso.[6] These constituted people who were forced to flee their homes due to violence, but remained in Burkina Faso. In an example of how regional instability results in refugee influx into Burkina Faso, there were 25,171 Malian refugees in the country.[7] Burkina Faso is also utilized by as a transit country for the migratory movements of other refugees northwards to other countries in Africa.

Political Conditions

Long-term political instability in the form of frequent military coups and presidential dictatorship came to an end following the overthrow of former president Compaoré’s 27-year regime in 2014, with a freer political environment ushered in in which opposition parties were able to consolidate popular support and contest free elections. Nevertheless, a democratic tradition of rotation of power between governing and opposition parties had yet to be firmly established. Although multiparty presidential and legislative elections were held in late 2015 ushering in a new civilian regime, due to the continuous security instability the prime minister and his cabinet resigned in January 2019, with Christophe Joseph Marie Dabiré becoming the new prime minister.

Attacks by jihadi terrorist groups which escalated around 2015, severely impede the government’s ability to govern and implement its policies in the unstable north and east.

This was especially the case following the January 2016 terrorist attack in Ouagadougou, in which more than 20 people were killed. Thus, a key challenge for any government that rules the country is the challenge of addressing the presence and violent activities of jihadi insurgent groups in the country.

Politically, according to Freedom House, despite holding competitive democratic multiparty elections in the recent period, Burkina Faso was judged as “partly free.” Its overall freedom score was 60 (out of 100), with political rights scored at 4 (out of 7), and civil liberties at 3 (out of 7).[8] Reasons for the relatively low freedom score include rule by a small educated elite, the military, and labor unions which have historically dominated political life. In another reason, the judiciary is a formally independent body, but has historically been subject to executive influence and corruption. Moreover, both the MPP and the UPC have extensive patronage networks and disproportionate access to media coverage, making it difficult for other political parties to build their support bases. In another reason, corruption is reported to be widespread, with anticorruption laws and bodies considered generally ineffective. In addition, the new electoral code passed in July 2018 was criticized by opposition parties for making it difficult for people living abroad to register and vote.[9]

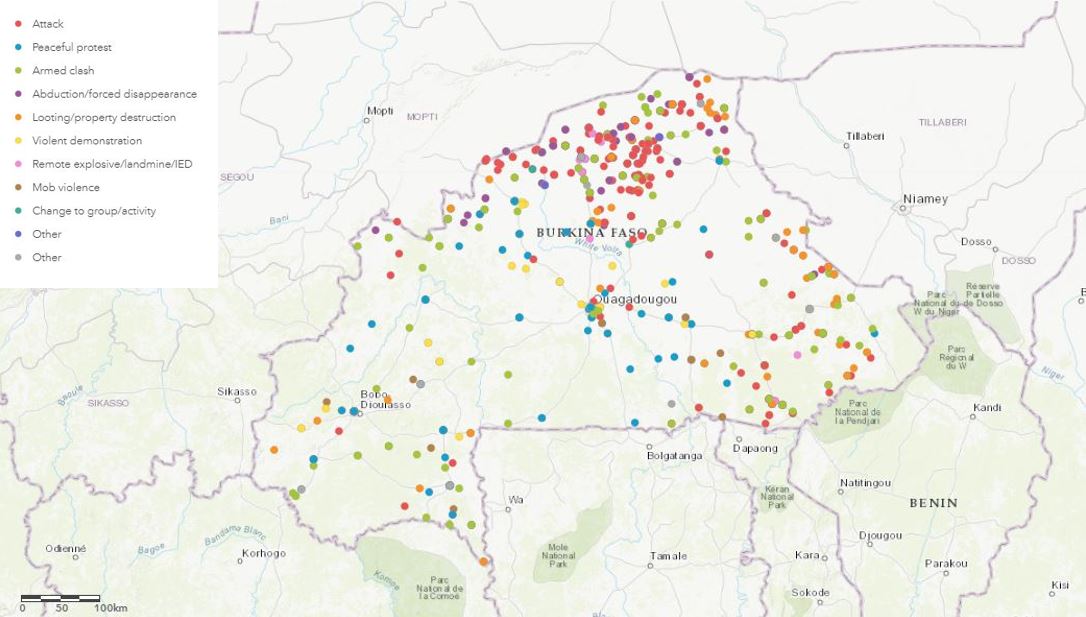

Security Conditions

Burkina Faso experiences a high degree of political instability, with security presenting a major challenge. The escalation in violent attacks in Burkina Faso is attributable to the weakening of the state over the past decade, particularly the frequent coups and the transitional governments that followed them and the sense that government has difficulty confronting the country’s multiple challenges. This was one of the reasons for the cabinet reshuffle in January 2019 when the ministers of defense and security were replaced, reportedly over the inability to counter the proliferation of regional and homegrown jihadi militias in the country, who exploit the combination of weak central power and local ethnic and religious divisions (such as the historical rift between the Fulani and the Rimmaybe communities) to conduct criminal pillaging and religiously motivated attacks against their adversaries. This includes targeting the country’s Christian communities, with the Catholic Church having a major influence on society and many of the country’s leaders having been Catholic, from Maurice Yameogo, the first civilian president, through the current president, Kabore. These jihadi attacks, thus, also represent the targeting of one of the Burkinabe society’s main pillars.

The political instability in neighboring countries, especially Mali, also affects Burkina Faso’s domestic instability. This was especially the case around 2015 when jihadi cross-border raids began from neighboring countries such as Mali into Burkina Faso, with the country experiencing a sharp escalation of attacks since then, especially in the northern and eastern regions. This was the case in August 2017 when a terrorist attack in Ouagadougou by a Mali-based al Qaida group. A motivating factor for the attack may have been Burkina Faso’s participation in the United Nation’s peacekeeping initiative in Mali, which reportedly “angered” al Qaida’s affiliate in the country.[10] In a later development, in December 2018 following a series of jihadi attacks against civilians in Arbinda’s Soum province, the country’s deteriorating security situation prompted the government to declare a state of emergency in several northern provinces bordering Mali, which was extended by six months in January 2019, with seven of the 13 administrative regions under a state of emergency.

Terrorist Groups

As discussed earlier, in 2015 regional jihadi terrorist groups began to intensify their activities in Burkina Faso. The major terrorist groups operating in the country include the al Qaida-affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), Ansar ul-Islam, and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS).

Ansar ul-Islam

The group is composed largely of Muslim Fulani and Rimaïbe tribesmen in Burkina Faso. It aims to take over part of the country’s north and apply a sharia Islamic regime in the area of what it considers the ancient Fulani Empire of Djeelgodji. It targets Burkinabe security forces and civilians primarily in the country’s northern Sahel Region.

ISGS

It aims to impose an Islamic state in the Greater Sahara region. It primarily operates in the Mali-Burkina Faso-Niger tri-border region.

JNIM

A branch of al Qaida in Mali, it aims to establish an Islamic state centered in Mali, where it operates primarily in the northern and central regions. It also conducts attacks in Burkina Faso and Niger.

Terrorism Incidents

Burkina Faso experienced an escalation of jihadi terrorist attacks around 2015. [Note that the group attribution for specific attacks is not always available in published news sources.]

October 9, 2015: An estimated 50 jihadi terrorists carried out an attack on a police station in Samoroguan, near Burkina Faso’s border with Mali, killing three police officers and wounding two civilians.

January 15, 2016: Three terrorists attacked the Cappuccino Turkish restaurant and the Splendid Hotel in central Ouagadougou, killing 30 people, including foreigners. More than 56 people were wounded. The terrorists took control of 176 hostages, which were released the next day following a confrontation with counterterrorism forces. The three terrorists were killed in the shootout. The attack was attributed to al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

December 16, 2016: A group of 30 gunmen, who had crossed the border from Mali into Burkina Faso the previous day, attacked a military base in Nassoumbou, killing 12 soldiers. Several military vehicles were also destroyed. Several military vehicles, weapons, uniforms, and other military materiel were seized by the attackers, who returned to their base in Mali’s Foulsaré forest. At this point, their announced the establishment of Ansar ul-Islam, as the first ‘homegrown’ jihadi group in Burkina Faso.[11]

Late March 2017: A combined French-Burkinabé counter-terrorism operation alongside the northern border with Mali killed Malam Ibrahim Dicko, the leader of Ansar ul-Islam.

August 13, 2017: Terrorists reportedly affiliated with AQIM attacked the Aziz Istanbul restaurant in Ouagadougou, killing 19 people, including 9 foreigners.

March 2, 2018: Eight terrorists, reportedly aligned with al Qaida, carried out an attack near the French Embassy and the Army Headquarters in Ouagadougou, killing 8 people, and wounding 80 people. The attackers were killed, as well.

May 2018: Al Qaida-linked terrorists carried out an attack in the Rayongo district of Ouagadougou. In the shootout with security forces, five gendarmes were wounded, as well as one civilian. The attackers were killed.

August 11, 2018: An attack by jihadis involving a bomb and shooting killed five policemen, including another person, near the Boungou gold mine, near Fada N’Gourma, in eastern Burkina Faso.

August 28, 2018: A roadside bomb near Fada N’Gourma in the Eastern Region struck a vehicle and killed seven members of the security forces.

October 4, 2018: A roadside bomb struck a military vehicle Gayeri in the east near the border with Niger, five soldiers and wounding another. Three attackers who reportedly were involved in the attack were killed.

December 27, 2018: JNIM terrorists carried out an attack in Sourou province, killing 10 gendarmes, and wounding three others.

April 26, 2019: Terrorists attacked the village of Comin-Yanga, Koulpélogo Province, killing five teachers.

April 28, 2019: Terrorists attacked a church in the town of Silgadji, near Djibo, Soum Province, killing at least 6 people.

May 12, 2019: Terrorists killed a Catholic priest and five worshippers in northern Burkina Faso, with their church burned.

May 14, 2019: Jihadi terrorists killed four Catholics in northern Burkina Faso.

May 28, 2019: Jihadi terrorists attacked a church in northern Burkina Faso, killing four people.

June 9-10, 2019: Jihadi terrorists carried out two attacks in the town of Arbinda, in northern Burkina Faso, killing 19 Christians and wounding 13 others on June 9, with another ten killed in the nearby Namentenga province the following day.

Counterterrorism Response Measures

Burkina Faso’s counterterrorism campaign is multi-pronged in response to the multi-faceted terrorist challenges facing it domestically and regionally.

The country’s military is the primary counter-terrorism service. The gendarmerie consists of 4,200 personnel, including a paramilitary security company that consists of 250 personnel.[12]

The government’s counter-terrorism campaign includes the launching on March 7, 2019 of an operation in the east that led to the arrest of approximately 100 jihadi terrorists.[13] This was followed by May 10by a counterterrorism operation in Burkina Faso’s northern regions.[14]

Burkina Faso is active in various regional counterterrorism cooperation initiatives. Its capital is the home base for a French Special Forces group, consisting of 250 personnel,[15] which has been deployed in the Sahel to fight the jihadi terrorist groups since 2010. This has also been part of Burkina Faso’s support of the French intervention in Mali in 2013, with the country contributing troops to the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA).[16]

The country also participates in the G-5 Sahel Joint Force to fight terrorism and criminal trafficking groups with regional neighbors Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, which is supported by European countries, particularly France and Germany. It also cooperates with France and Mali in tackling the Islamic threat, as seen in “Operation Panga” in April 2017, in the area straddling the border shared by Burkina Faso and Mali, which succeeded in killing Malam Ibrahim Dicko, Ansar ul-Islam’s leader.[17]

In addition to France, Burkina Faso’s counterterrorism measures are also assisted by the United States.

Burkina Faso has also been the largest contributor of troops to the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). With 1,886 personnel deployed, this accounted for about one-fourth of the country’s defense forces.[18]

In another regional counterterrorism cooperative program, from mid-February to early March 2019, Burkina Faso hosted “Flintlock 2019”, a multinational military exercise involving some 2,000 military personnel from about 30 African and western partner nations.[19]

Crime

Crime in the form of armed robberies, street crime, roadside banditry, and kidnappings of foreigners is pervasive in Burkina Faso.

Foreigners engaged in tourism, humanitarian aid work, journalism or business, are especially targeted. As of mid-2019, several Western hostages kidnapped in Burkina Faso were still being held by jihadi terrorist groups.

A select listing of incidents involving the kidnapping of foreigners, include the following:

April 2015: Jihadis abducted a Romanian Romanian security guard at the manganese mining site in Tambao.

January 2016: Two Australian nationals were abducted by Al-Mourabitoun, an al Qaida-linked group, in the northern town of Djibo near the border with Mali. One of the kidnapped persons was later released.

September 2018, A jihadi group kidnapped two foreign nationals in the north.

Mid-December 2018: A Canadian and an Italian were kidnapped in southwest Burkina Faso.

January 15, 2019: A Canadian citizen was kidnapped near Gayeri in the Est region and found dead near the Niger border 2 days later.

May 11, 2019: Four hostages, including westerners, were rescued during a French military operation in northern Burkina Faso. Two of the rescued hostages were French tourists who had been kidnapped from Pendjari National Park in Benin on May 1, 2019.

Future Trends

Certain economic, political, and security trends will likely significantly impact Burkina Faso’s future.

Economic Trends

In the short-term, the implementation of the National Economic and Social Development Plan (PNDES) in 2019 is expected to promote some degree of economic growth through public investment to upgrade the country’s infrastructure. In another area, the implementation of the three-year 2018-2020 International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) economic program, is expected to enable the government to reduce the country’s budget deficit while maintaining spending levels on social services and investments in the country’s infrastructure, particularly in poor regions affected by terrorist insurgencies, although major positive impact is expected to take several years.

Political Trends

The March 2019 constitutional reform measures approved by the National Assembly include an amendment to limit the length of a presidential term to two consecutive terms of five years (10 years in total). This is expected to result in greater political stability, especially in the aftermath of the next presidential elections scheduled for November 2020, when President Kaboré will run for re-election.

Diplomatically, in May 2018 Burkina Faso severed its diplomatic ties with Taiwan, a long-term historical ally. As a result, China reopened its embassy in Ouagadougou, which had been closed for 24 years. This is expected to upgrade the political, diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries, including an increase in trade and funding for counterterrorism initiatives, such as the G5 Sahel force.

Security Trends

The country’s fragile security situation is likely to remain a primary future challenge. The G5 Sahel force is still in its beginning stages and it is expected to take several years before it becomes effective in mounting counterterrorism operations.

Finally, the ability of the government to reduce the current escalation in jihadi terrorism, particularly its geographic spread, is a major challenge. This includes curtailing the ability of the jihadi groups to radicalize and reshape the communities in the areas where they operate. Their attacks against the country’s Christian communities is another area of concern, including the possibility that it might lead to further internal displacement and turmoil.

Recommendations for Improving Current Situation

Stability in Burkina Faso, as with its neighbors, will be achieved if the combined cooperative efforts of regional and foreign actors, especially France and the United States, as well as international organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, succeed in helping to resolve the country’s myriad political, socio-economic and security problems.

-FWS

[1] http://www.fao.org/3/i3760e/i3760e.pdf.

[2] https://borgenproject.org/facts-about-poverty-in-burkina-faso/.

[3] http://www.fao.org/3/i3760e/i3760e.pdf.

[4] file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/1518183366%20(1).pdf.

[5] https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/bfa/.

[6] https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/69819.

[7] Ibid.

[8] https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/burkina-faso.

[9] Ibid.

[10] https://www.foxnews.com/world/new-al-qaeda-cell-forms-in-burkina-faso-as-terror-group-cements-foothold-in-africa.

[11] https://ctc.usma.edu/ansaroul-islam-growing-terrorist-insurgency-burkina-faso/.

[12] The Military Balance 2018 (Routledge, 2018), p. 449.

[13] https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/traveladvisories/traveladvisories/burkina-faso-travel-advisory.html.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Military Balance 2018, p. 449.

[16] https://ctc.usma.edu/ansaroul-islam-growing-terrorist-insurgency-burkina-faso/.

[17] https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3964.

[18] https://ctc.usma.edu/ansaroul-islam-growing-terrorist-insurgency-burkina-faso/.

[19] https://www.dvidshub.net/news/311065/more-than-30-nations-kick-off-flintlock-2019-burkina-faso-mauritania.